Leah Nagely Robbins

I traveled to Truth or Consequences, New Mexico on September 29, 2023 – what would have been my dad’s 82nd birthday, though he’s forever 63 in my mind. I didn’t know he would show up so fully with me on this trip to New Mexico.

From Albuquerque, my plan was to visit the wetland habitat of Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge in Socorro County, about halfway to T or C. In the midst of the Chihuahuan Desert, this 30,400 plus acre refuge provides a permanent home to some and a welcome respite for migrating birds in just 10 miles along the Rio Grande.

A man walked toward baggage claim wearing a black tee with white all cap letters centered on his chest:

PROUD

HUNTER

Another man pulled a large cooler sealed with duct tape from the luggage carousel. Others carried long packages. In line for the rental car. I watched another man waiting for an SUV, decked out in denim, a knife attached to his belt, wearing a mashup of cowboy and hiking boots. September 29th is the start of muzzle hunting deer season in New Mexico.

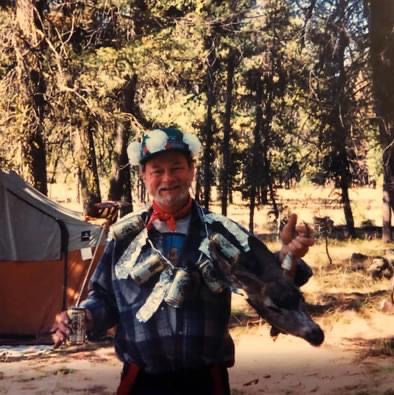

This felt like home. I never hunted with my dad and rarely saw him on his actual birthday because he would be setting out in his big blue rig, an SUV from another time, driving through the countryside east of the Cascade mountains in a high desert prairie at the edge of a national forest to meet up with his buddies for deer season in Oregon on September 29th.

The drive south on Interstate 25 was new territory for me, as was the 75 mph speed limit. Mountains to the east and west and vast unpopulated desert, the road plunged over and through steep canyons, with windsocks accompanying signs warning “Gusty winds may exist.”

A very large brown and white sign for the Very Large Array, a National Radio Astronomy Observatory, popped up before my planned exit to the Bosque del Apache refuge. I first heard about the Very Large Array from a science nerd friend from New Mexico. The sign jogged my memory, I had to follow it. Decelerating from 80 plus mph to 40 for the sharp curving exit sent my lunch of nuts, cranberries, cheese, and salami flying.

“Go til ya know, right Dad?” I didn’t stop for directions and my data was low so Google Maps was of little help.

I turned right onto a local road following a pickup and soon enough a smaller green and white sign with only a left arrow and three letters VLA appeared. Another sign to follow. This road headed west through a village past an American Legion outpost, a local tire repair shop with an assorted pyramid leaning against the building. There were no more VLA signs, so I made mental notes of my turns in reverse like a middle-aged Gretel. I came to a huge four way stop the size of an interchange, but in the distance loomed a rock outcropping – not quite a mountain – more than a hill – with antennae at the top I noticed faintly from the freeway. The story I told myself was that the Very Large Array must be at the top. I went straight and followed the road, narrowing as it continued its climb. It curved and switched from asphalt to packed gravel.

“OK I doubt this road handles trucks on their way to maintain the big equipment,” I said to myself. Next to the road were homes, trailers, and yards full of detritus. The road got windier and steeper and switched from packed gravel to dirt before a “Dead End Approaching / Private Road” sign appeared.

“Hey Dad, looks like I found the end of the road!” He would have kept going until an actual fence or gate meant the real end, but I played it safe.

As I backed up, turned around and headed down hill I noticed a pit or a quarry filled with shiny angular black rock, like an outcropping of broken vinyl records. I couldn’t process fast enough to tell if it was native rock or if it was a dumping ground for old asphalt.

I followed the breadcrumbs back to the highway, wondering if I was far from VLA or if it was just down the next turn. Either way, I was off to Bosque del Apache National Wildlife Refuge.

Driving slowly down the one-way tour road I saw only 3 other cars and 2 people with huge telescope lenses hunting birds with their cameras. My arm dangled out the window to feel the afternoon sun and the soft kind of breeze that happens at 10 mph, not a skin whipping on the highway.

Exploring these new places felt familiar in the way we used to explore dead end gravel roads in Oregon forests. I felt Dad with me, but this time I was in the driver’s seat. I carried on a one-way conversation, also typical with Dad, pointing out how a section of the refuge reminded me of the day we trekked through dense brush between the Bay Ocean spit road to the Pacific Ocean. We were far from the ocean today.

I kept my eyes open for habitat and was rewarded with interesting tree snags, darting vesper sparrows, floating hawks, and roadrunners. I stopped when I wanted to and listened to the wind. The insects were louder than the birds, louder than the wind, humming like a high voltage transmission line with its magnetic fields vibrating coiled wire.

After settling in to T or C, meeting my fellow Wayward Writers, I hatched a plan to return north to find the Very Large Array. With the benefit of WiFi I found I was 50 miles off from my initial trek, and to go back for a day trip from T or C would be a 5 hour round trip commitment. Maybe it was the completist in me, or the kind of curiosity Dad shared with me, or the call of the high speed freeways with an unlimited miles rental car, but I had all Sunday afternoon. A fellow writer’s spouse joined me as co-pilot and navigator.

Over more mountains and scrub brush desert lay a plateau of an ancient lake bed where 27 individual radio telescopes stand in one of four configurations, pointed in the same direction, combining their individual range to act as one, more powerful telescope. We arrived on the last day of “Configuration A” when they are spread the furthest apart in a “Y” pattern that extends over a diameter of 22 miles. Within the next week they will move using a rail truck that picks each 230 ton structure off its mounting post and carries them to their new location miles away.

The data the Array amasses is used to map and measure magnetic fields, turning radio light into images to explain and understand deep dark mysteries across galaxies like the size and strength of black holes.

The mechanics and electronics are a sort of black box to me, the way they transfer this from space through these huge machines into bits of data. The mysteries of the universe may never be fully understood. I suppose my electrical engineer dad may have been able to understand better and translate for me. I’ll remain curious and look and listen for the connections across the gulf of space between tiny atoms and enormous galaxies.

Leah Nagely Robbins is a writer, civil engineer, and musician based in Portland, Oregon. Her work has been published in Tangled Locks Journal, Open Secrets, and Reading and Traveling.