By Ariel Gore

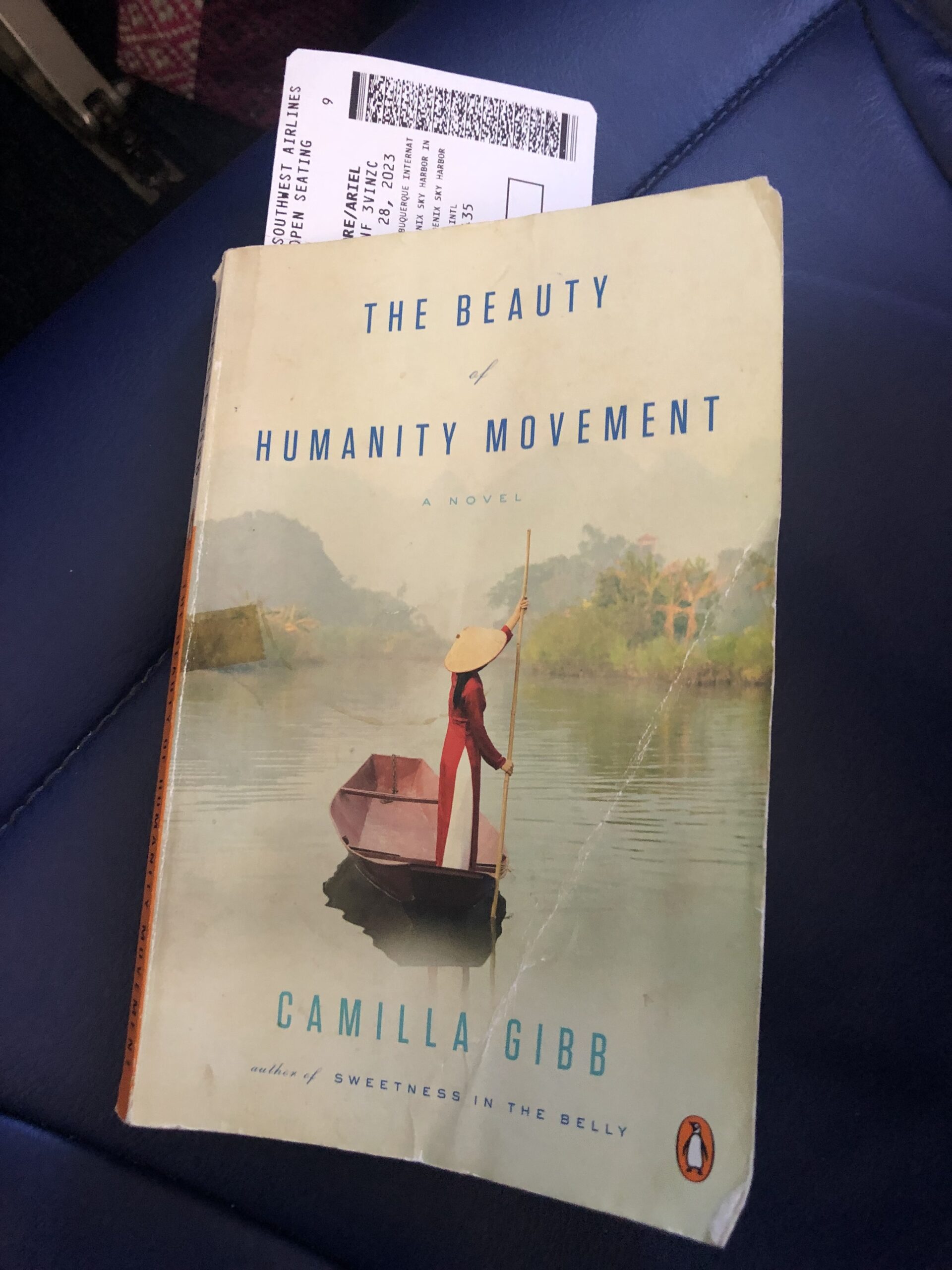

The Beauty of Humanity Movement by Camilla Gibb turned up in the little library in my front yard in Santa Fe in early autumn. I set it aside for myself as I stocked the blue shelves with other titles. Inside, I added it to the row of books next to my bed—a “meaning to read soon” placement. I puzzled at the title from time to time. Maybe it meant the book would praise the beauty of people’s ability to migrate?

I’ve moved so much in my life. As writer and a queer, I’m the classic profile of pre-gentrification. We don’t mean to do it, but capitalism creates the pathways that will serve it (and not us) in the end: Artists and lesbians soften up working class neighborhoods before the money moves in—displacing us even as we displaced the previous poor schmucks.

This morning on the way to the airport I grabbed The Beauty of Humanity Movement—basically an afterthought. No Modernism Without Lesbians was too thick to fit in my backpack.

As I sat in my aisle seat reading, I merged into the world of an unlicensed pho shop in Hanoi. The street chef, Old Man Hung, didn’t have his own restaurant anymore, but he still made his soup every day; the heart of his community.

Even as I read about Hanoi, I was thinking about Portland—a place I once called home, a place I didn’t mean to get priced out of, a place I was just visiting now.

The food scene in Portland is Brooklyn-level these days, but when my daughter and I first moved there in 2000, not so much. I mean, it had an okay breakfast game, and plenty of dive bars. The salty cheese on the nachos cut the sour of my whiskey cocktails. There was one Mexican place on Alberta. But that seemed like pretty much the size of it at first. A town built for graveyard-shift workers.

In the early pages of The Beauty of Humanity Movement, it takes Old Man Hung “several attempts to get his fire started in the damp air, but as the dark grey of night yields to the lighter grey of clouded morning, the flames burn an orange as pure and vibrant as a monk’s robe.” Gibb’s writing sings like that.

Pho, the national soup of Vietnam, originates in Hanoi. A thousand years of occupation by the Chinese left rice noodles commonplace. Later, the French colonization would fire up a taste for beef stew. “We’re clever people,” Hung’s Uncle Chien explains to him in the novel. “We took the best the occupiers had to offer and made it our own.”

I hope we brought and left something good to Portland in our years there.

My daughter and I wanted badly to love Portland, but the truth is we felt a little bit displaced when we got there. The colleague/acquaintance who’d convinced me to make the move turned out to be kind of a vampire. We wandered through the clouds and the gentle rain, homesick. But one day—what’s that delicious smell? At once earthy and smoky, and was that cardamom? Inside a simple-looking restaurant, the broth simmered, enticing.

“The smell of home was indistinguishable from the smell of leaving home: each inhalation a mix of familiarity and fear.”

Camilla Gibb, The Beauty of Humanity Movement

Now my plane descended into the Portland grey.

It turns out The Beauty of Humanity Movement title actually refers to a movement—like an art movement, or a political movement—but it’s “The Beauty of Humanity” Movement. Who wouldn’t want to be a part of that movement?

In the novel, an art curator named Maggie from Minneapolis has returned to her parents’ homeland in search of her missing artist-fathers’ legacy. Perhaps, someone finally tells her, the old man with the pho cart remembers him. His old restaurant used to serve as a meeting place for dissident artists and movement-members.

I could practically smell it through Gibb’s prose: The fresh beef, the chopped green herbs, the fresh basil and jalapeño, the fish sauce and the hint of star anise.

The first time my daughter and I visited Portland, before we made the move, I gazed at all the big wooden houses that lined the rainy streets here. Maybe in Portland, I could finally have a house with a pointy roof. Maybe here I could give my daughter everything I felt I was supposed to. Maybe our house would have a porch.

In Portland, we did find a small community of dissident artists. For what the town lacked in hip restaurants back then, it more than made up for with utopian dreamers and punk potlucks. It took three years to finally afford a little house with a pointy roof in Portland. No porch, but it did have a mudroom. One of its selling points, as far as my daughter and I were concerned, was its excellent proximity to Pho Hung.

I checked into my Airbnb in the darkening afternoon, called Pho Hung right away. It’s true that sometimes the smell of home is indistinguishable from the smell of leaving home and of visiting a place that will never be home again—that mix of familiarity and fear.

In The Beauty of Humanity Movement, Maggie and her new friend, Old Man Hung, along with a tour guide named Tu, wonder if this is what it feels like to have a family.

Book: The Beauty of Humanity Movement

Author: Camilla Gibb

Rating: 5 Traveling Shoes

Existential question the book leaves you with: What does it mean to be part of a legacy?